Readers of this blog may remember in the first post Introduction - On lost lineages and legacies

the statement on "military research interests" which led to its creation and, subsequently, the extensive quoting from sources such as independent Army historian William A. Ganoe to set forth and explain the beginning tragedy which led to U.S. Regular Army units losing, for the first time, the bulk of its War of Independence heritage (by the rules of the lineage and battle honors game); and again, following the Second War of Independence, losing it through an illogical and incoherent re-organizational scheme. As Ganoe framed the 1815 situation:

"In the war just passed the army had played its part in burlesque and tragedy. It had been more pitiful than in the Revolution. Yet when the affair was over, the country did not absurdly disband its entire force, principally because there was the fresh memory of a sound spanking. Instead a law was passed limiting the army to 10,000 men and a corps of engineers....Some sinister effort must have been at work to deprive all the old regiments of their traditions and spirit. For no plan could have more shrewdly dammed any existing pride and affiliations than the following:

The old 1st Infantry went into the new 3rd Infantry;

the old 2nd went into the new 1st;

the old 3rd, into the new 1st;

the old 4th, into the new 5th;

the old 5th, into the new 8th;

the old 6th, into the new 2nd;

the old 7th, into the new 1st; and

the old 8th, into the new 7th.

The new 1st was then made up of the old 2nd, 3rd, 7th and 44th;

the new 2nd, of the old 6th, 16th, 22nd, 23rd, and 32nd;

the new 3rd, of the old 1st, 17th, 19th, and 28th;

the new 4th, of the old 12th, 14th, 18th, 20th, 36th, and 38th;the new 5th, of the old 4th, 9th, 13th, 21st, 40th, and 46th (revised correction in 1949?)

the new 6th, of the old 11th, 25th, 27th, 29th, and 37th;

the new 7th, of the old 8th, 24th, and 39th;

and the new 8th, of the 5th, 10th, 15th, 31st, 33rd, 34th, 35th, 39th, 41st, 42nd, 43rd, 45th.

The eight remaining infantry regiments were smaller than their war predecessors because, although the number of companies in each remained at ten, every company contained 78 men instead of 103. There was no effort to preserve the honors or traditional numbers of any of the prewar regiments. The 1st was merged with other regiments and re-designated the 3d, and the old 2d, 3d, 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th were likewise lost in the remains of disbanded regiments. The new numbers were founded on the seniority of the colonels, the senior colonel commanding the 1st, and so forth. As a consequence of the reduction, 25,000 infantrymen were separated from the service. Another consequence was that the form of the infantry establishment was set roughly for the next thirty years. Not until the Mexican War, thirty-one years later, was it substantially expanded. Not only were the units of the army diabolically jumbled but its size had to shrink to about one-sixth its former self. Officers and men had to be ejected and the remainder readjusted with a natural wrecking of ambition and spirit. Neither was their any solace to the remnants in being sent in small scattered fractions to lonely frontier posts and seacoast fortifications" p.147

- William A. Ganoe, The History of the United States Army, (Appleton Century Company, NY, 1942 )

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Turning to my recent "find." It contains a very interesting discussion on the reduction of 1815, and what the author believed should have happened, written in the wake of the Army's organizational schemes and perceived failures in conjunction with the Mexican War.

De Bow's Review, Volume 15 (Google eBook)

James Dunwoody Brownson De Bow and others, 1853

http://books.google.com/books?id=4Z0RAAAAYAAJ

For those not interested in reading the full article, here are some key extracted excerpts:

Art. II.—THE ARMY OF THE UNITED STATES. MILITARY EDUCATION REGULAR TROOPS AND VOLUNTEERS, ARMY ORGANIZATION, ETC.

A Great improvement in the military intelligence of the country has been apparent, since the first battles of the Rio Grande, in the late war. It is now generally conceded by military men —including all the well-informed of the officers of volunteers— that experience in service and instruction, either at the military school or in the field, are requisite qualifications for command.

It is admitted, in short, that while our citizens in arms have more efficiency, their lives are safer under the direction of men who have some knowledge of service in the field, than under those who are without any, whatever may be their personal qualities or civic distinction.

At the declaration of the war which is called our second war of independence, we had the amount of twelve regiments then in service—estimating the artillery of twenty companies as a double regiment—to wit: one regiment of light artillery, one of light dragoons, the two of artillery, seven of infantry, and one of riflemen. The youngest of these had been organized and in service four years. Can any one doubt that if these regiments had been filled to the war establishment, and assembled in a division of twelve thousand men, under any general-in-chief (having only a firmness of purpose equal to that of Henry Dearborn), it would have been sufficient to overcome any forces which the enemy possessed, or had at any time collected, in Canada? Had this little army been formed into brigades, and commanded by their rightful, though casual, seniors—as was the case at the commencement of the late war, under Gen. Taylor (himself a brevet brigadier),—and the general staff selected from the officers then present, inclusive of the Corps of Engineers,—how long would the posts of Montreal and Quebec have stood uncaptured before it? The regiments of volunteers, and those called "year's men," subsequently raised, could have been more fitly, and less expensively, employed in the local defences of the country. This appeared to have been the design of the War Department, in the first organization of the nine military districts; but there seems to have been no unity of plan, at any time, in the councils of the government.

"What an economy of expenditure would have resulted from this course!

The constitutional objection with some of our State troops—so disreputable to the government of a republic—to crossing its boundary, would in such case also have been avoided.

Experience and Science Necessary

A brief view of the course which was pursued in conducting that war will readily account for the exhaustion of the treasury, and of nearly all the government's credit; and from commencing at the extremity of the line, instead of advancing on the main posts at the centre, with the essential defect of organization, to which reference is made, may be easily understood the causes of our disastrous failures.

It is a fact, that after nearly two years of the war had expired, we had scarcely one general officer qualified to lead a brigade, until such of the colonels of experience, as Macomb, Thomas A. Smith, Bissell, Gaines, and Scott,* were promoted; Pike and Covington having been killed, and Cushing assigned to the defence of a district.

Can there be a doubt that for the command of a division, a brigade, a regiment, or a company, an officer of twenty, ten, or three years' experience in service, will be superior to one who has been but twenty, ten, or three months in commission? The proposition is so simple, that it would seem to require an apology for stating it—it being recollected that war is truly called an art—that no human art was ever acquired by intuition— and though battles have been won under tyros, or men without instruction, no exception can be deduced from these; for certainly there is no science, art, or craft, in which man's capacity can be developed, without preparatory trial or training.

A free display of the knowledge and ability possessed by an be attained by adequate experience and the full practice of discipline; and the longer the experience and the more the practice, the greater, of course, will be the self-reliance and self-possession. It is preposterous to expect that a citizen, whatever may be his personal bravery, can exhibit such qualities in his first engagement, or on his first command of men in action. He may exhibit rashness—of which numerous instances will at once occur to the memory; and many instances, too, of the consequent waste of his men's lives will be recollected. Thus it will ever be found that in those parts of battle-fields where have been displayed the least military foresight and skill, there will be the greatest destruction. of life, with the least success, not alone to be accounted for by the superiority of an opposing force. Such may be assumed to have been the case, from the representations of officers of the volunteer regiments themselves, on the luft of our line in the victory of Cerro Gordo. And in parts of the great battles of the Valley of Mexico, instances can be named where the superiority of opposing forces could not have been sufficient to account for the partially disastrous results....

The great names also of Brown and Jackson, under whom the reputation of our country for superiority in arms was first established, may be cited as exceptions to the rule requiring

....

* Of the other officers, who had been in service before the declaration of war, and were subsequently distinguished in the grades they held, either in battle or by being selected for staff commissions, the following names were entirely overlooked at the time of the appointment of general and field-officers for the new levies, required for immediate and efficient service:

[Of Field-Officers:) Kingsbury, C. Freeman, Backus, Milton, James Miller, Fenwick, McEea, Nicoll, Stoddard, Bowyer, Laval, Eustis, Floyd, Posey, and Geo. Gibson.

Of the Artillery: (Capts.) Read, N. Freeman, Beall, Whiley, Wollstonecraft, House, [prom, in 1813,] Walbach, A. B. and Geo. Armistead, Wilson, E. Humphreys; (Lieuts.) Hanks, Gates, Gansevoort, Provcaux, Bennett, E. A. Allen, Darragh, Lomax, Sat. Clark, Fay, M. Mason, Vandeventcr, Fitzgerald, Ewing, Sands, T. J. Beall, and Ezra Smith.

Of Light Artillery: (Capts.) Macpherson, J. N. Mcintosh, McDowell, L. Leonard; (Lieuts ) Melvin, Thornton, Stribling, Boisaubin, Ketchum, Arms, Irvine, J. R. Bell, Murdoch, Randolph, W. F. Hobart, and Sumter.

Of Light Dragoons: ("Capts.) Helms, Hayne, Halsey, Cummings; (Lieuts.) Littlejohn, Haig, Hukill, Boardman, Kean, H. Whiting, and Birch.

Of the 1st Infantry: (Capts.) J. Whistler, Heald, Clemson, Swan, Pinkney, Stark, Hughes, Baker; (Lieuts.) Whitlock, Symmes, Knight, Kingsley, H. Johnson, Brownson, T. Hamilton, Albright, Ostrander, Perkins, Helm, Bryson, Page, Campbell, Stansbury, Vasquez, and Bissell.

Of the 2d Infantry: (Capts.) Boote, Campbell, Arbuckle, Carson, Pratt, Brevoort, Miller; (Lieuts.) Chambcrlin, Luckett, Peyton, Pemberton,Warc, Davis, Brownlow, Wirt, H. Bradley, Willis, Villard, and Bliss.

Of the 3d Infantry: (Capts.) Bird, Nicks, Atkinson, Woodruff, Clinch, Dinkins; (Lieuts.) H. G, White, W. S. Hamilton, Butler, Chotard, Herriot, Laval, and Morley.

Of the 4th Infantry: (Capts.) Cook, Prescott, Snelling, Barton, Adams, Fuller; (Lieuts.) C. Larrabee, J. L. Eastman, Peckham, Gooding, Bacon, and Greenhough.

Of the 5th Infantry: (Capts.) Bankhead, Johnson, Brooke, Whartenby, Chambers, Dorman; (Lieuts.) Opie, R. H. Boll, R. Carson, Jamison, and Saunders.

Of the 6th Infantry: (Capts.) Beebe, Machesney, Nelson, Arrowsmith, G. Humphreys, Walworth, Muhlenberg, Sterry; (Lieuts.) Ed. Webb, Shell, and Thompson, [since killed in Florida.]

Of the 7th, Infantry: (Capts.) Blue, Oldham, Dohcrty, Cutler, Z. Taylor, [since President,] Overton, C. Nicholas, A. A. White; (Lieuts.) Broutin, Robinson, Waide, Vail, G. O. Allen, and E. Montgomery.

Of the Riflemen: (Capts.) Sevier, McDonald, Forsyth, H. R. Graham, Visscher, Hays, L. Morgan, Appling; (Lieuts.) Josh. Hamilton, Patterson, Ramsey, and Smyth.

No more gallant and accomplished officers than these could be found in any army in the world....

...The few (of the officers then in service not named in the list preceding) who were honored with higher commissions in the new regiments, were all, who were living, retained by the Board of Generals, at the reduction of the army, with their advanced rank. And several of those named in the list, who were subsequently advanced, were also retained in the same manner. But it will be admitted by all who have any personal knowledge of the officers passed over, that any of them— referring to the greater part—would have been equally distinguished, and rendered as valuable service to their country, if the same opportunity had been afforded them, by the same appreciation of their merits. A consideration of the highest importance—indeed the only one—for it is not pretended that these officers had any claim individually, beyond their right to promotion in their several corps—is the confident Relief and reliance, that in the future engagements with the enemy, very different results would have been accomplished...

At the conclusion of that war, when the great reduction of the army took place, the organization of a permanent peace establishment was finally adjusted in the councils of the nation, having a wise view to the most effective preparation for future war. The theory of a distinguished statesman[Calhoun], who succeeded to the direction of the war department, was adopted,—to preserve such a general staff, and a skeleton of corps for the line, as could, in the event of war, be most promptly enlarged to a full and effective war establishment. But what has been exhibited on the occurrence of the event contemplated? When the late war broke out, and the legislative power was called into action, the whole theory, so obviously suited to the purpose then to be effected, was almost entirely disregarded. After the provision for recruiting an increase of the rank and file, the 'skeleton' was left to act by itself; and when officers were required for the additional forces to be raised, the officers of the old corps were left as they were, with their existing companies and corps!

We had then, besides the corps of the general staff, fourteen regiments in service; all the officers of which were more regularly trained and accomplished than those of any other army in the world,—for no family influence, royal or noble, had ever interfered with their just advancement—(the rules of promotion having been enforced by the Senate.) The battles of Palo Alto and La Palma had been fought, when there were eleven new regiments added to the army—which were officered, as of old, from civil life! The result was, that out of two hundred and sixty-four appointments, of the rank of field-officers and captains, but seven were taken from the army,* and less than twenty selected from the thousands of retired officers of great merit and experience; some of whom had been distinguished in the field; and would eagerly have engaged in the new war, with the mere advancement in rank to which they were entitled, granting that they were not made subordinate to those who had no pretension to the rank conferred. Of the volunteer regiments, the officers were principally chosen by the volunteers themselves, and they, were commissioned, of course, by the state governments; but there were more men of military education chosen for the volunteers, than there were in the regular regiments. Some of those from the army, who received appointments in the new corps, were of undoubted merit; but they were all indebted to the favor of influence "at court" for their preferment.

* These were Colonel Andrews, (Paymaster;) Lieut.-Colonel Fremont, (Second Lieut, and Brevet Captain of Topographical Engineers.) Lieut.-Colonel Graham, (Brevet Major of Infantry, of thirty years' service ;) Lieut -Colonel Johnston, (Captain Topographical Engineers ;) Major F. Hamilton, (a first Lieut, of Dragoons;) Major Taicott, (first Lieut, of Ordnance;) and Major Woods, (a (Captain of Infantry.)...

What is the secret of the so unvarying good conduct and prowess displayed by our regular troops, in the battles of the Rio Grande (and no other description of troops was there), conquering a superior and well-organized force, commanded by the ablest of the Mexican generals? It is, that every officer in our line, of all the grades of rank, was conscious that he held the precise position to which he was entitled,—no room being left for any impulse, but that of displaying to his superiors his best ability and gallantry, and winning for his corps and his country the greatest triumph.

If the military establishment of the.republic had been kept distinct, and men of political ambition had not been translated to it, there would never have been any interference by military men with political affairs; and our peace establishment, as we have endeavored to show, could have been made amply sufficient for any future military service, which would ever be required on this continent. A military institution to be efficient, must always be conducted on principles essentially repugnant to these of free government; and therefore the profession of arms ought, under such a government, to be kept carefully distinct, as well as subordinate. The case of Washington, it was admitted by all, stood alone; and could never be made a parallel for the position of any future military chief, under the Constitution. But as statesmen have committed the first error, and politicians have adopted the last, for the facility of popular management, it only remains for us to abide the consequences....

REMARKS.

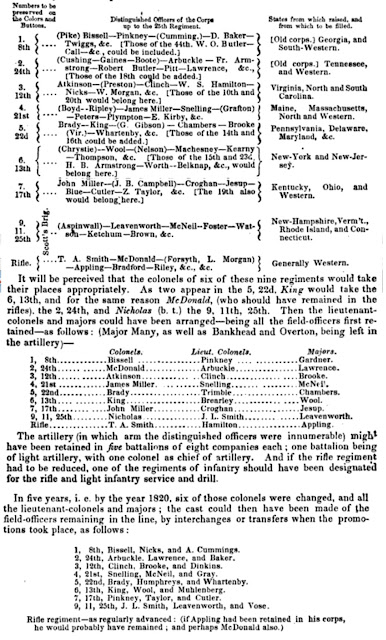

It has long been an impression of the writer, that on the reduction of the army, at the peace of 1815, the esprit du corps, so highly estimated and carefully cherished in every service but ours, might have been made available, not only as a future incentive of pride and emulation in the regiments retained, but to add greatly to the inducement and facility of enlistment among the people of the several states; so essential a want, whenever the crisis demands a sudden increase of the regiments to a war establishment. It was simply by preserving the numbers of the distinguished regiments, and those from which distinguished officers had arisen; and by arranging the officers retained, as near as might be, to their former numbers. Though the time has elapsed when this can be done, yet every reader who has been in the service, will take an interest in the following project: which, it will be perceived, has a double relation to the states from which the regiments, were originally raised, and to the distinction they acquired, both by their members individually, and as corps....

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

actual reorganization as stated in the 1815 Army Register for comparison with above-

A compilation of registers of the army of the United States, from 1815 to 1837 (inclusive.), United States. War Office, William A. Gordon

http://books.google.com/books?id=XIcFAAAAMAAJ

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Remarks continued:

If this organization and arrangement had obtained (with the same officers who were in service), the reduction and derangement which took place in 1821 would not, in all probability, have been passed by Congress. It is easy to perceive how much more readily inclined the country and its representatives would have been, to preserve the distinguished numbers of these regiments, and to resist their reduction, with the powerful influence they would have had from the pride of the states. In the event of war, when the increase of the establishment became necessary—under the same influence, and the influence of wisdom in sustaining the best interests of the country, the advantage would have been secured to the existing establishment, of enlarging the corps on these numbers, and even, with the omitted numbers, of forming a brigade of each. The officers of these could have supplied, at least, the field-officers and captains of seventeen full regiments. From the efficient officers who had retired, during a long peace, from the army, after a public notification had been issued by the war department, a selection, for reappointment in the enlarged or added corps, could have been made ; with a stipulation, by legal provision, that no retired officer should be appointed to a higher grade than that he would have held had he continued in service.

Previously to such enlargement, on the first occurrence of a war, as in that of 1846, though but few of the officers of the old corps continued in the field, and the esprit du corps became, as it were, traditional—if the same prowess and gallantry displayed by the officers then engaged had been achieved under the organization proposed, with the designated numbers preserved—what might not have been the enthusiasm felt and expressed throughout the country for the accumulated glory of these corps!

A political objection may be raised to this plan of organization—that it might lay the foundation of sectional jealousy and division; but it will be found, on further examination, that it would result in the reverse of an objection, and produce advantages. In the event of a "rebellion," it would furnish the means of avoiding the use of that corps of troops which may appertain to the section involved; and in the case of servile'" insurrection," vice versa.

The chief officers of the several departments of the government, under the President, are selected and appointed in reference to the different sections of the country. There is sufficient unity and nationality in the Supreme Court, though strictly constituted from the several sections of the Union. And in the cabinet council, there has been no want of nationality, though in its formation the sections are regarded.

Excepting the navy, whose organization seems best adapted to its destination, the army is the only institution in the organization of which the sections are not regarded; and is, of course, without the benefit of sectional interest in its preservation, and without that powerful incentive in the separate corps to noble emulation and achievement....

There is another method by which a more effectual inducement and facility could be given, throughout the interior of the country, to enlistments, and thereby effect a two-fold advantage—first, to secure its influence for the great desideratum of more rapid enlistments; and secondly, to improve thepersonnel of the ranks, and thereby lessen the enormous evil of desertion,—an evil for which no remedy, in the least effective, has ever been devised. It is, to select, out of the forty sergeants and non-commissioned staff of each regiment, three or four, annually, for promotion to brevet second lieutenants, the selection being made on the recommendation of their commanders. It is well understood, that the officers of the army, generally, arc opposed to this measure; they say, that old non-commissioned officers, of great merit, arc rendered valueless when made commissioned officers. This may be true, in reference to the old sergeants; but not to the young, who have sufficient education. If you expect ever to draw into the ranks of your regular regiments the young men of spirit and ambition, who are natives of the soil, you must furnish them some inducement and opening for the exercise of their ambition. Furnish them, at least, the prospect ot meeting, in a portion of the ranks of each company, a few of their own caste, with whom they can associate, without feeling that they have degraded themselves to the level of the slaves of the old world, or the refuse of our populous cities; and can thus be saved from the insuperable inclination to desert on the first opportunity. The military institution is necessarily the same in all countries; but it is believed that, for some years past, there are more non-commissioned officers in the British service annually promoted in the same number of regiments than in ours. It is an example which should not be contemned in the government of a republic.

Whether, in connection with this proposition, the thought could be entertained of limiting the Military Academy to the instruction of cadets solely for the scientific corps, inclusive of the artillery ;—whether, in that case, a surplus number would be requisite, from which a selection could be made, leaving a portion to be disbanded at every annual examination—or otherwise, whether such an organization could be given to the scientific and staff corps, as to commence their first appointments with the grade of captain, or first lieutenant, in each; so that all vacancies might be filled by selection of the most competent from all the subalterns of the army—with, perhaps, a previous trial "on extra duty," as formerly in those corps—are suggestions which may be left to the future influence of military intelligence and economy over the law-making and executive authorities.

A great objection to any change touching the organization of the army, or its system of government, is the vacillation it causes, in addition to that already of record, in the legislation of Congress; by which changes heretofore, and the mode of carrying the laws into effect by executive acts, the consequences have been, to depress the pride of the corps affected, and injure the spirit and efficiency of the army. An exhibit of all the acts passed by Congress for changes of organization, increase and reduction of the army, brought together in a tabular abstract—as will be seen prefixed to the Dictionary of the Army under notice—will surprise the reader, whether a military man or statesman. The present organization has continued longer than that of any former period; and having shown its efficiency so admirably through the Mexican war, in the general system of the staff departments, as well as in the different arms of the line, it will evidently be best to preserve it as it is.

--------

DeBow's Review was a widely circulated magazine of "agricultural, commercial, and industrial progress and resource" in the American South during the upper middle of the 19th century, from 1846 until 1884....contained everything from agricultural reports, statistical data, and economic analysis to literature, political opinion, and commentary. wiki

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

DeBow's Review was a widely circulated magazine of "agricultural, commercial, and industrial progress and resource" in the American South during the upper middle of the 19th century, from 1846 until 1884....contained everything from agricultural reports, statistical data, and economic analysis to literature, political opinion, and commentary. wiki

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The next big reduction, of course, was in 1821. Readers of the blog will recollect that this was when the unique and elite Rifle Regiment, of 1808-1821, was disbanded.

December 1820 - "..out there the army, having passed through its nameless period, was growing in quality while the government was looking with skeptical eyes at its size. It was too much to expect over 7,000,000 people to support 10,000 soldiers." Ganoe, p. 157

Jackson's own "plan for the reduction of the army" in 1820 would have left the Rifle Regiment intact.

The Papers of Andrew Jackson: 1816-1820, Andrew Jackson, Sam B. Smith, Harriet Fason Chappell Owsley, Harold D. Moser, Univ. of Tennessee Press, Aug 14, 1994 - 700 pages - p. 387

http://books.google.com/books?id=JxA1t3UD9qwC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA387#v=onepage&q&f=false

According to a recent interpretation by David and Jeanne Heidler, the real impetus behind the reduction of 1821, had more to do with fears of a potential Caesar [Jackson] and his control of the standing army, then pure budget cutting motives in the wake of the financial panic of 1819.

http://books.google.com/books?id=K5Xhnu1AAU8C&lpg=PP1&pg=PA228#v=onepage&q&f=false

for an excellent summary of this period and issues at play see

Bradon J Smith: Thesis Beyond Politics: The Political Development of Presidential Signing Statements in Historical Context

http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/77616/1/bjsmit.pdf

by B Smith - 2010 - pp. 6-18

"The Act “To reduce and fix the Military Establishment of the United States” of March 2nd 1821 called for a mass reduction in the officer corps and reassignment of responsibilities to lower officer grades. It also shifted the conflict over military administration from a military-civilian axis to that of an executive legislative battle.

The Congress’s initial intent for the legislation was that power be diminished at the expense of the military, not the executive branch. After Jackson had so clearly thumbed his nose at his superiors and, in the eyes of many legislators, attempted to build a cult of loyalty within his officer corps, many politician’s minds turned to the classical history of Caesar’s tactics and feared that Jackson could potentially head a military coup.[12] This is certainly reflected in the provisions of the legislation that would pass both houses and receive the president’s endorsement. p. 10

December 1820 - "..out there the army, having passed through its nameless period, was growing in quality while the government was looking with skeptical eyes at its size. It was too much to expect over 7,000,000 people to support 10,000 soldiers." Ganoe, p. 157

Jackson's own "plan for the reduction of the army" in 1820 would have left the Rifle Regiment intact.

The Papers of Andrew Jackson: 1816-1820, Andrew Jackson, Sam B. Smith, Harriet Fason Chappell Owsley, Harold D. Moser, Univ. of Tennessee Press, Aug 14, 1994 - 700 pages - p. 387

http://books.google.com/books?id=JxA1t3UD9qwC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA387#v=onepage&q&f=false

According to a recent interpretation by David and Jeanne Heidler, the real impetus behind the reduction of 1821, had more to do with fears of a potential Caesar [Jackson] and his control of the standing army, then pure budget cutting motives in the wake of the financial panic of 1819.

http://books.google.com/books?id=K5Xhnu1AAU8C&lpg=PP1&pg=PA228#v=onepage&q&f=false

for an excellent summary of this period and issues at play see

Bradon J Smith: Thesis Beyond Politics: The Political Development of Presidential Signing Statements in Historical Context

http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/77616/1/bjsmit.pdf

by B Smith - 2010 - pp. 6-18

"The Act “To reduce and fix the Military Establishment of the United States” of March 2nd 1821 called for a mass reduction in the officer corps and reassignment of responsibilities to lower officer grades. It also shifted the conflict over military administration from a military-civilian axis to that of an executive legislative battle.

The Congress’s initial intent for the legislation was that power be diminished at the expense of the military, not the executive branch. After Jackson had so clearly thumbed his nose at his superiors and, in the eyes of many legislators, attempted to build a cult of loyalty within his officer corps, many politician’s minds turned to the classical history of Caesar’s tactics and feared that Jackson could potentially head a military coup.[12] This is certainly reflected in the provisions of the legislation that would pass both houses and receive the president’s endorsement. p. 10

...Throughout this debate it is clear that the end of the conflict with the Seminoles, the securing of Florida, and the nation’s debt were the key conditions that precipitated in the proposal of the legislation. After each substantial conflict in the history of the young American state, most notably the War of 1812, similar actions were taken. But by no means do these rationales preclude the consideration of Andrew Jackson’s conduct as an important factor between both proponents and opponents of the military reduction. Was Jackson an indispensable general, who had delivered the nation from the hands of the British and protected further protected it from the attacks of the Seminoles? Or was he an overzealous, firebrand, whose ambition resembled that of a rising tyrant? These were certainly open questions in the minds of many American statesmen in 1821 and though Jackson’s conduct was not the centerpiece issue of this legislation, it certainly was paramount in the consideration of the bill and key to understanding the contemporary political context of the actors’ actions.

...Despite the fact that Monroe had found a place for Jackson to continue his service, that did not keep him from registering his objections to the legislation after endorsing it. It is these dichotomous elements of endorsement and objection by which historical and legal scholarship has identified his “Special Message” of January 17, 1822 as a “signing statement”....p. 12

But upon examination of the origin of the 1821 Act “On fixing the nation’s military peacetime establishment” one begins to understand how Monroe’s actions were interpreted as a twofold subversion of the Congressional will. The legislative body certainly was suspicious of the idea of a large, peacetime standing body, and the professional officers that were characteristic of it. In addition to this general suspicion the Congress had taken note of the conduct of Andrew Jackson, and was well aware that the proposed legislation likely would have been pushed out from military service by an administration agreeing to abide by the legislatively mandated reduction. Monroe in his second message noted the somewhat absurd notion that the “defender of New Orleans” might be driven of the nation’s service and writes of the other arrangements had been made.[37] p.17

...But it is not solely recognition of Jackson’s importance that Monroe battled with Congress, but due in large part to a desire to protect the executive prerogative in administration of the military. Monroe routinely cites the spirit of the legislation and the Constitution in giving the president appointment power, and he sought to protect this privilege, regardless of what Jackson’s recommendations were.

...The victories of Jackson in [The War of ] 1812 and his securing of Florida from the continental powers created a new sense of military nationalism that was coordinate of the “Era of Good Feelings.”[40] However, Monroe’s signing statement highlights new internal political battles. Among institutions, conflict existed between the executive and legislative branches over military administration. Amongst men, it pitted would be presidents in the legislative branch, such as Clay, versus a would-be military general turned president, Andrew Jackson, whose victories had brought about a new nationalist culture. Monroe, less concerned with his future and more so with the security and administration of the American state, sought to protect this national sentiment as a condition important for collegial government and “Republican Saints” lest the nation be split by renewed faction and sectionalism. He did not seek to protect Jackson for Jackson’s own sake.

Additionally, the military had been the most instrumental in securing American security and domination on the continent, requisites for the forthcoming Monroe doctrine, treaties with the British after the War of 1812 and the Spanish after Jackson’s acquisition of the Florida territories was only achieved after victory.

...Thus the examination of Monroe’s signing statement reveals not a mere disagreement with Congress but a profound tension in purpose, scope, and power. To be certain, the executive branch was jealous of its control of the military and eschewed any congressional fetters. The Congress was likewise suspicious of the military and the executive branch in its efforts to consolidate power. Though the judiciary is absent from this particular battle, the philosophical principles of the founders and the system set forth by the Constitution are clearly evident in this particular examination of the signing statement. The legislative and executive branches are naturally at tension with one another and act to check the other’s power. It’s a struggle that is central and fundamental to understanding American history, the breadth of which is impossible to capture in hundreds of books. Signing statements are just one element of this narrative, and this section, focusing on the very first, demonstrates how this idea of executive-legislative tensions is evident even in an “Era of Good Feelings.” p. 18

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* General Jackson was utterly opposed to this reduction of the army. A Mr. Humphrey, of New Tork, describes a letter received by his brother from General Jackson: "The letter alluded to was written about the time when the last reduction of the army took place: it is at my command, and although I do not feel justified in placing it before the public, I will mention some of the most striking features it presents. Among other expressions he says, in express terms—' the government ought to be d——d—instead of reducing the army in a republic like this, it should bo increased tenfold.' He ridicules the idea of depending upon our militia, speaks of reducing them to a proper state of subordination as an impossibiity, and of their utter inefficiency in cases of emergency! He dilates on the extent of our frontier, and the extreme impropriety of leaving our remote posts with the inadequate garrisons to which they are necessarily reduced in consequence of the diminution of the army. In fact, the general tenor of the letter is that of decided and bitter animadversion upon the measures pursued by the general government.—New York American, October, 1828.

It had long been the intention of General Jackson to resign his commission in the army as soon as the difference with Spain should have been brought to a peaceful conclusion. An important reduction in the army,*[see above] long contemplated, was effected in the spring of 1821, and left the General without an adequate command....His mode of bidding farewell to the army...was in the terms following:

"HEADQUARTERS, DIVISION OF THE SOUTH,

"Montpelier [Alabama], May 31, 1821.

"This day, officers and soldiers, closes my military functions, and, consequently, dissolves the military connection which has hitherto existed between you and myself, as the Commander of the Southern Division of the army of the United States. Many of us have passed together days of toil and nights of vigilance. Together we have seen the termination of one British and two Indian wars, in which we have encountered fatigues, privations and dangers. Attachments and friendships formed by associations of this kind are the most durable, and my feelings will not permit me, in retiring from military command, to take a silent leave of my companions in arms.

"Justice to you and to my own feelings requires that I should place before our common country the testimony of my approbation of your military conduct, and the expression of my individual regard. Under the present organization for the reduction of the army, agreeably to the act of Congress, many valuable officers who have served with me have been suddenly deprived of the profession which they had embraced, and thrown upon the world. But let this be your consolation, that the gratitude of your country still cherishes you as her defenders and deliverers, while wisdom condemns the hasty and ill-timed policy which has occasioned your disbandonment; and that, too, while security was yet to be given to our extensive frontier, by the erection of the necessary fortifications for its defense, greatly extended as that frontier has been by the recent acquisitions of the Floridas. But you, fellow-soldiers, have that which can not be taken from you—the consciousness of having done your duty, and with your brother officers who are retained, of having defended the American eagle wherever it was endangered.

"To you, my brother officers, who are retained in the service of your country, permit me to recommend the cultivation of that harmony and friendship towards each other which will render you a band of brothers. It is your duty so to conduct yourselves on all occasions as that your enemies shall have no just cause for censure. It ought to be borne in mind that every captain should be to his company as a father, and should treat it as his family—as his children. Continue, then, as heretofore, when under my command, to watch over it with a father's tenderness and care. Treat them like children, admonish them, and if, unhappily, admonition will not have the desired effect—coercion must. The want of discipline and order will inevitably produce a spirit of insubordination, as destructive to an army as cowardice, and will as certainly lead to disaster and disgrace in the hour of battle: this, as you regard your military reputation and your country's good, you must prevent. Imploring from heaven a blessing upon you all, I bid you an affectionate adieu.

"Andrew Jackson, "Major-General, Commanding the Division of the South."

Life of Andrew Jackson, by James Parton Mason Brothers, 1861, pp. 589-591

http://books.google.com/books?id=bGYFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA589#v=onepage&q&f=false

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Contrast the above with today; when our political/military seniors, in lock-step, willingly vouchsafe the administration's line on downsizing and continued gender-military experimentation!

NO MORE dire and deadly battles to be fought by infantrymen, with their accompanying stark deprivations, sometimes fighting for mere survival against the elements, as well as a formidable enemy. Study but a few of our "ancient battles" of Guadalcanal, Buna, Tarawa, Gela, Salerno, Bernhardt Line, San Pietro, Cassino, Anzio, D-Day through Break-out, Mytchkina, Peleliu,The Bulge, Leyte, Saipan, Guam, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Taejon, Pusan, Naktong, Hoengsong, Chosin, Kunu-ri, Chipyong-ni, Blood Ridge, Heartbreak Ridge, Ia Drang, Khe San, Dak To, Tet, Hamburger Hill, Mogadishu, Roberts Ridge....to name but a countless few...

Yes, we've come a long way baby!

Rangers (and Rangerettes), Lead The Way!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

...The victories of Jackson in [The War of ] 1812 and his securing of Florida from the continental powers created a new sense of military nationalism that was coordinate of the “Era of Good Feelings.”[40] However, Monroe’s signing statement highlights new internal political battles. Among institutions, conflict existed between the executive and legislative branches over military administration. Amongst men, it pitted would be presidents in the legislative branch, such as Clay, versus a would-be military general turned president, Andrew Jackson, whose victories had brought about a new nationalist culture. Monroe, less concerned with his future and more so with the security and administration of the American state, sought to protect this national sentiment as a condition important for collegial government and “Republican Saints” lest the nation be split by renewed faction and sectionalism. He did not seek to protect Jackson for Jackson’s own sake.

Additionally, the military had been the most instrumental in securing American security and domination on the continent, requisites for the forthcoming Monroe doctrine, treaties with the British after the War of 1812 and the Spanish after Jackson’s acquisition of the Florida territories was only achieved after victory.

...Thus the examination of Monroe’s signing statement reveals not a mere disagreement with Congress but a profound tension in purpose, scope, and power. To be certain, the executive branch was jealous of its control of the military and eschewed any congressional fetters. The Congress was likewise suspicious of the military and the executive branch in its efforts to consolidate power. Though the judiciary is absent from this particular battle, the philosophical principles of the founders and the system set forth by the Constitution are clearly evident in this particular examination of the signing statement. The legislative and executive branches are naturally at tension with one another and act to check the other’s power. It’s a struggle that is central and fundamental to understanding American history, the breadth of which is impossible to capture in hundreds of books. Signing statements are just one element of this narrative, and this section, focusing on the very first, demonstrates how this idea of executive-legislative tensions is evident even in an “Era of Good Feelings.” p. 18

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* General Jackson was utterly opposed to this reduction of the army. A Mr. Humphrey, of New Tork, describes a letter received by his brother from General Jackson: "The letter alluded to was written about the time when the last reduction of the army took place: it is at my command, and although I do not feel justified in placing it before the public, I will mention some of the most striking features it presents. Among other expressions he says, in express terms—' the government ought to be d——d—instead of reducing the army in a republic like this, it should bo increased tenfold.' He ridicules the idea of depending upon our militia, speaks of reducing them to a proper state of subordination as an impossibiity, and of their utter inefficiency in cases of emergency! He dilates on the extent of our frontier, and the extreme impropriety of leaving our remote posts with the inadequate garrisons to which they are necessarily reduced in consequence of the diminution of the army. In fact, the general tenor of the letter is that of decided and bitter animadversion upon the measures pursued by the general government.—New York American, October, 1828.

It had long been the intention of General Jackson to resign his commission in the army as soon as the difference with Spain should have been brought to a peaceful conclusion. An important reduction in the army,*[see above] long contemplated, was effected in the spring of 1821, and left the General without an adequate command....His mode of bidding farewell to the army...was in the terms following:

"HEADQUARTERS, DIVISION OF THE SOUTH,

"Montpelier [Alabama], May 31, 1821.

"This day, officers and soldiers, closes my military functions, and, consequently, dissolves the military connection which has hitherto existed between you and myself, as the Commander of the Southern Division of the army of the United States. Many of us have passed together days of toil and nights of vigilance. Together we have seen the termination of one British and two Indian wars, in which we have encountered fatigues, privations and dangers. Attachments and friendships formed by associations of this kind are the most durable, and my feelings will not permit me, in retiring from military command, to take a silent leave of my companions in arms.

"Justice to you and to my own feelings requires that I should place before our common country the testimony of my approbation of your military conduct, and the expression of my individual regard. Under the present organization for the reduction of the army, agreeably to the act of Congress, many valuable officers who have served with me have been suddenly deprived of the profession which they had embraced, and thrown upon the world. But let this be your consolation, that the gratitude of your country still cherishes you as her defenders and deliverers, while wisdom condemns the hasty and ill-timed policy which has occasioned your disbandonment; and that, too, while security was yet to be given to our extensive frontier, by the erection of the necessary fortifications for its defense, greatly extended as that frontier has been by the recent acquisitions of the Floridas. But you, fellow-soldiers, have that which can not be taken from you—the consciousness of having done your duty, and with your brother officers who are retained, of having defended the American eagle wherever it was endangered.

"To you, my brother officers, who are retained in the service of your country, permit me to recommend the cultivation of that harmony and friendship towards each other which will render you a band of brothers. It is your duty so to conduct yourselves on all occasions as that your enemies shall have no just cause for censure. It ought to be borne in mind that every captain should be to his company as a father, and should treat it as his family—as his children. Continue, then, as heretofore, when under my command, to watch over it with a father's tenderness and care. Treat them like children, admonish them, and if, unhappily, admonition will not have the desired effect—coercion must. The want of discipline and order will inevitably produce a spirit of insubordination, as destructive to an army as cowardice, and will as certainly lead to disaster and disgrace in the hour of battle: this, as you regard your military reputation and your country's good, you must prevent. Imploring from heaven a blessing upon you all, I bid you an affectionate adieu.

"Andrew Jackson, "Major-General, Commanding the Division of the South."

Life of Andrew Jackson, by James Parton Mason Brothers, 1861, pp. 589-591

http://books.google.com/books?id=bGYFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA589#v=onepage&q&f=false

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Contrast the above with today; when our political/military seniors, in lock-step, willingly vouchsafe the administration's line on downsizing and continued gender-military experimentation!

NO MORE dire and deadly battles to be fought by infantrymen, with their accompanying stark deprivations, sometimes fighting for mere survival against the elements, as well as a formidable enemy. Study but a few of our "ancient battles" of Guadalcanal, Buna, Tarawa, Gela, Salerno, Bernhardt Line, San Pietro, Cassino, Anzio, D-Day through Break-out, Mytchkina, Peleliu,The Bulge, Leyte, Saipan, Guam, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Taejon, Pusan, Naktong, Hoengsong, Chosin, Kunu-ri, Chipyong-ni, Blood Ridge, Heartbreak Ridge, Ia Drang, Khe San, Dak To, Tet, Hamburger Hill, Mogadishu, Roberts Ridge....to name but a countless few...

Yes, we've come a long way baby!

Rangers (and Rangerettes), Lead The Way!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment